Common Misconceptions About Violin/ Viola Technique (And What I Learned From Dancers)

Share

by Rozanna Weinberger

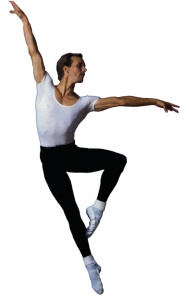

Going to school at Juilliard, the music majors were often surrounded by dancers, actors in the school cafeteria. I remember how easy it was to distinguish the dancers from musicians for strictly on appearance. While a clear give away for dancers was their lean limbs, they always managed to carry themselves with amazing posture . Turns out theres much to learn about how dancers move and how these observations can improve string playing. Sure I may never wear a pair of point shoes or a tutu, but if a dancers craft is built on moving with ease, efficiency and beauty there may be lessons for the string player as well.

It’s true they often held themselves with an almost rigidly perfect posture, even when eating lunch, but turns out all

that training was so they could do what they do at the optimum level – move beautifully and for the most part using their physique to maximize the potential of movement. Dancers couldn’t possibly do what they do on stage if they hadn’t been trained to use their bodies as efficiently and ‘naturally’ as possible. Just as ‘naturals’ are the ultimate in string players, dancers no doubt strive to move their bodies to optimize balance, strength and beauty.

Learning movements, for all human beings begins at birth, from an infants’ learning to roll from side to side in a crib to eventually attempting to crawl on hands and knees, eventually managing to balance on feet, putting one in front of the other to walk. The arms learn to flow while the muscles seem to act and react simultaneously. Indeed these seemingly easy tasks for adults took much trial and error as infants, where the brain learned from each fall and every movement that caused physical stain, to move better and with ease.

A common misconception among string players is that sloping shoulders and posture comes with The territory and has no real effect on playing. Sure its’ tiring to sit in an orchestra for hours at a time or to be on ones feet for hrs. standing in front of music and playing. But should slumping be part and parcel to playing? And is it possible that learning to open out chest and shoulders ultimately makes playing easier? Chances are dancers don’t slouch because its not as pleasing aesthetically but it’s also not the most efficient way to use ones’ body.

- A simple arching and curling motion study can facilitate in accessing the potential of the upper body. Start by clasping the hands together and putting them behind the neck at the nape just below the skull.

- Curl the rib cage as the abdominal muscles press into the spine. Notice how the arch is emphasized as the abdominal muscles press into the spine.

- Now move into the opposite of curling by arching the back and spine in the opposite direction towards the back. It is key to lengthen the space between the vertebra while at the same time arching the back. It is to not simply stretch from midway down the back but to lengthen that portion of the torso as well. It is helpful to think of ‘lifting the heart’ to get a sense of the lengthen and range of motion in the torso and our ability to open out the chest rather than cave it inwards.

- Because the hands are behind the neck, this is useful for isolating the movement of the torso and allowing the arms to go along for the ride.

What all this is leading to is the possibilities of the bow arm when the overall frame is not torqued in a curve but rather responsive to gravity. While fatigue and lack of strength in certain muscle grroups can exasperate slumping, simple awareness observations, and physical warm up, can assist one in this endeavor.

BUT WHY IS THIS IMPORTANT TO BOW TECHNIQUE YOU ASK?

How we orient the upper arm in relation to the bow determines whether a sound is ‘pressed’ or ‘spun like silk’. If the upper arm is torqued forward (which is a natural reaction to curving or slumping the upper body then ones sound will also tend to be pressed because the chance of crushing the sound is greater. (Imagine what would happen if one pressed the weight directly into the bow/instrument. Yes bow speed ensures a decent sound can be achieved but the more that sound is produced from vertical force to the string, the more likely one will crush the sound and potential resonance of the instrument. Further, while its possible to compensate for this more difficult way of moving the arm in general, there are easier ways to orient the arm for optimal technique, depending on the relation of the the upper arm to the forearm and bow.

The simple act of hanging the arm to the side then rotating the arm from the shoulder towards the back then forwards is a clue to the range of motion in the arm, specifically the upper arm. This potential to rotate the upper arm back can be cultivated, and will become a natural counter to the tendency of the bow hand and forearm to swivel in the opposing direction, causing one to lean bow arm weight on the index finger.